Zipf’s law is a constant curiosity for urban observers. According to the law, the size of a city (i.e. population) is inversely related to the city’s population rank. This implies that the largest city is twice as large as the second largest city, three times as large as the third largest city, and so on.

The fascinating thing to me (and many others) is nothing preordains this relationship. No central planner makes it happen; no individual is responsible for this relationship. Yet, it persists.

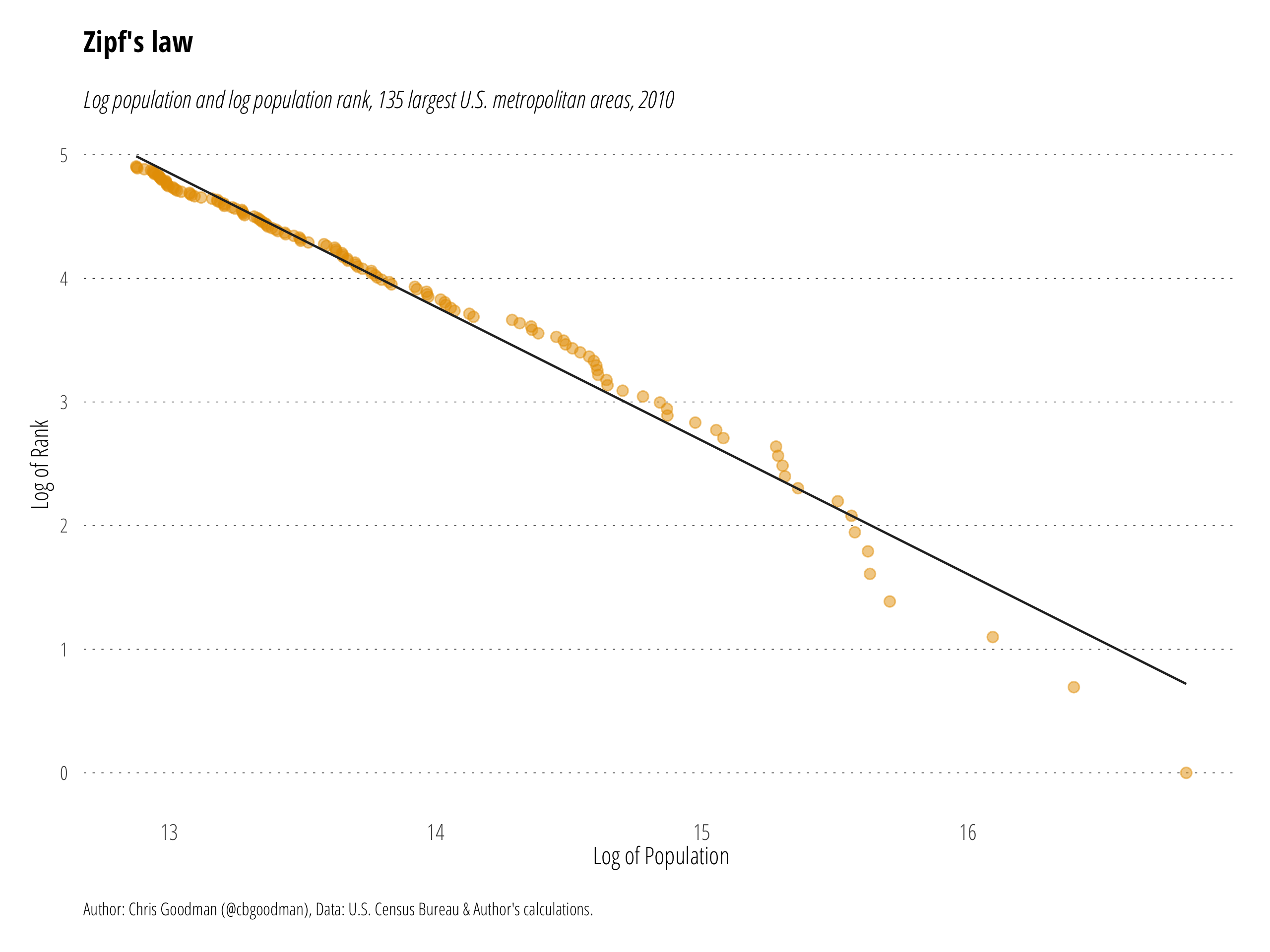

Below, I replicate Figure 1 from Gabaix (1999) by plotting the logarithm of size rank against the logarithm of size (i.e population) for the largest 135 metropolitan statistical areas in the U.S using 2010 census data (rather than 1991 data). We can see the typical downward sloping relationship found by Gabaix and others. Gabaix suggests the slope of the regression line should be roughly one and this is replicated, albeit slightly more negative than what was found using the 1991 data.

If Zipf’s law is to be believed, the above graph suggests that the largest cities (those with low log rank on the right side) are too small to fit Zipf’s law perfectly. They fall below the trend line and should be, in a perfect Zipf’s law world, larger than they actually are. This likely comports with the general understanding that large, coastal U.S. cities aren’t growing nearly fast enough to accommodate all the individuals who might want to locate there.

As Ed Glaeser notes, it appears that Zipf’s law for cities is a function of the outward growth of cities. When examining fixed boundary geographies, Zipf’s law appears not to apply. Therefore, the sprawling nature of many U.S. cities appears to be a fundamental part of Zipf’s law holding.

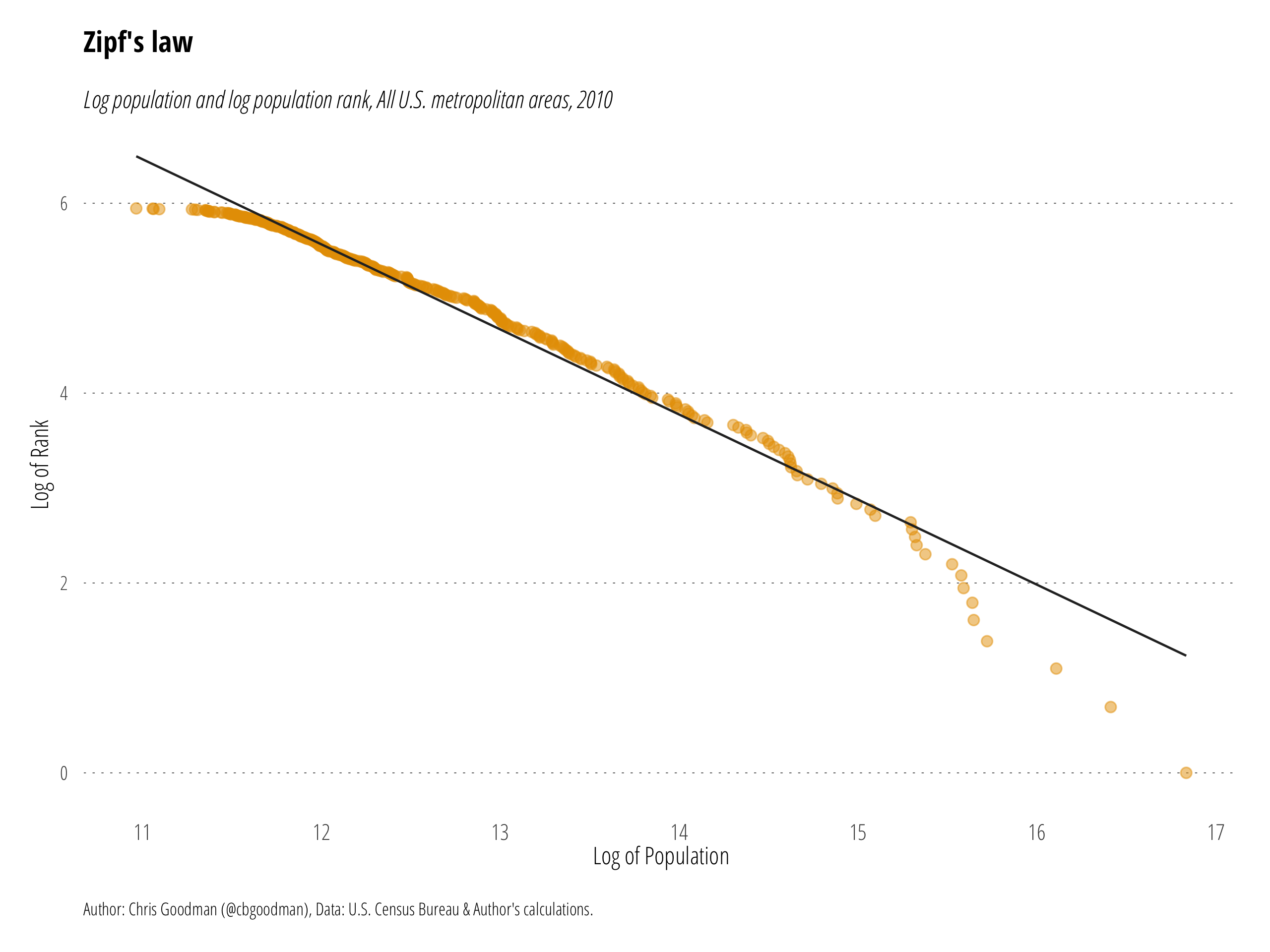

When expanded to the full data on all 382 metropolitan areas, things change slightly but the more or less linear relationship between rank and size is preserved. In this instance, both the largest and the smallest metropolitan areas appear to be too small to fit Zipf’s law. This is a trend noted by Ed Glaeser as well.